Jonathan C. Lewis

Author and Artist

Hats On

A fictional travelogue; four minutes to read.

My father’s hairline receded in his thirties, scalping his forehead into the color of bleached palm fronds—the kind harvested to weave straw hats. In my forties now, in my father’s genetic footsteps, my hair is starting to thin.

For his 35th birthday, I bought my dad a Panama straw hat. He never wore it. On scorching hot days or in the rainiest rain, it remained at home. I never thought to ask why. After he died, I found it stored in a well-traveled steamer trunk alongside a handful travel brochures for cities with free factory tours.

My dad loved factory tours. Growing up, we traveled to Detroit to see cars manufactured, to Virginia for cigarette assembling, to the Jelly Belly headquarters to watch jelly beans gel, to the United States Mint to learn how money is printed.

"Factory tours," he'd say with provoking eyes, "are biographies about the things we use. If objects could read and write, factories would be their memoirs, their histories."

When I’m on a factory catwalk, watching an artisan in his workshop, visiting a painter’s studio or taking a behind-the-scenes theater tour, I’m walking with my dad. Like him, I have a curiosity about the machines, inventions and gadgets that make up the world around me.

My name is Noah. When I chose a career teaching high school history, I launched a lifelong factory tour to see how the world was put together. To understand how things are birthed. Maybe to understand where I fit in, and what turns my gears.

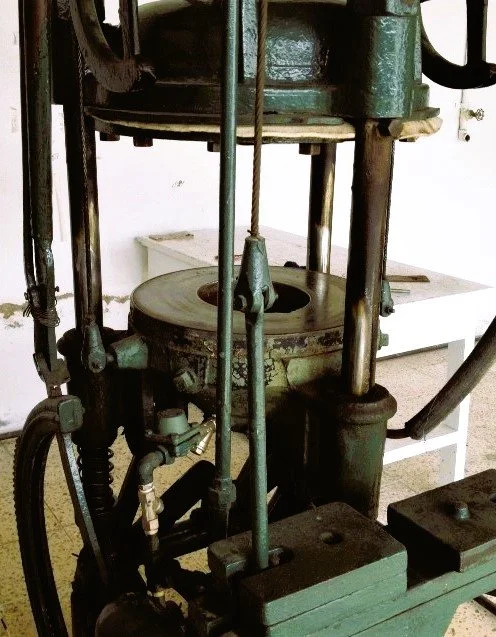

In Cuenca, Ecuador, the sweltering afternoon sun is slow-cooking me as I enter Homero Ortega, the world-renowned Panama hat factory. Inside, colorful hats are drying on the cool concrete floor. The sweet, grassy scent of toquilla straw fills the air. Workers block and cut woven straw with practiced precision, their hands sewing up the rims.

“In the 1940s, Panama hats comprised twenty-three percent of Ecuador’s total exports, employing a quarter of a million artisans,” my guide explains. “Today, 10,000 people weave, tighten, shape, dye, mold and press hundreds of thousands of hats per year.”

In the history of product branding, the Panama hat deserves a gold medal for misinformation. A Panama hat is not Panamanian. Panama hats—every single one of them—are handmade in Ecuador.

In the early 1900s, entrepreneurial Ecuadorians marketed lightweight, durable hats to fair-skinned Panama Canal workers in need of sun protection. By the time the Canal was completed, the practical and stylish straw sunhats were forever misbranded as Panamanian.

My father’s words come back to me. "Baby oil isn't made from babies, and buffalo wings don't come from flying buffalos," he’d say, his voice mimicking a Bob Hope one-liner. "Get behind the façade, question the brochure, go inside the factory. Find things out for yourself," he used to tell me.

Pulling me out of reverie, my guide is asking, "Would you like to try one on?" A cream-colored hat with a black ribbon band is in his hand. I examine the fine weave, the careful craftsmanship. I shake my head, answering, “No, gracias.”

Later, walking on the crooked, cobbled streets leading into the heart of Cuenca, I reach into my totebag and pull out my dad’s hat—the one he never wore. I place it on my head. It fits.